Around the time of my son E.’s first birthday he took charge of managing his separation anxiety, conquering fear, and developing a capacity for courage. How exactly did he do that, you ask? Well, we’d been reading lots of books together about animals, and making the requisite oink-oink here, baa-baa there, and moo-moo everywhere to help him learn to communicate in sounds and words. I noticed that he jumped every time I made the rather dramatic ROAR! for the lion. He loved my lion, and he feared my lion at the same time.

Coinciding with my efforts to help him develop the capacity for language, we’d played plenty of “Peek-a-Boo” and his brain had developed, like most other infants around eight months, the capacity for object permanence. E. could retain and utilize visual images enough to understand that I could go away, out of sight/sound/touch, but still exist in memory. As he developed language over the next year, around eighteen months he began begging me, “Be lion, Mommy.” When I turned to him and roared in his face, he looked at me without recognition at first, startled, eyes wide, and then he’d place his sweet hands on my face and say, “Be Mommy!”

Eventually, this game evolved over the coming months whereby he would ask me to approach him, then chase him, with “Come Lion.” As soon as I would reach him, after roaring whilst I covered the distance between us, he would say “Go Away Lion!” Then, urge me in the sincerest, anxious, heart-breaking voice, to “Be Mommy ‘gain.” It probably seems a masochist game to play, but trust me he was mastering fear. He was rehearsing the limbic pathways to both experience and calm fear synapses provoking sympathetic nervous responsiveness. He could turn on the fear “Be the lion”, and turn it off “Be my mommy again.” Abracadabra, I’m in control of my fear and my fate.

E. was also learning to handle the short periods of separation distress evident in secure attachments between parent and child. According to adult attachment researcher and associate profession in the University of Illinois Department of Psychology, Chris Fraley (2010):

Bowlby observed that separated infants would go to extraordinary lengths (e.g., crying, clinging, frantically searching) to prevent separation from their parents or to reestablish proximity to a missing parent. At the time of Bowlby’s initial writings, psychoanalytic writers held that these expressions were manifestations of immature defense mechanisms that were operating to repress emotional pain, but Bowlby noted that such expressions are common to a wide variety of mammalian species, and speculated that these behaviors may serve an evolutionary function.

Bowlby argued that, over the course of evolutionary history, infants who were able to maintain proximity to an attachment figure via attachment behaviors would be more likely to survive to a reproductive age. According to Bowlby, a motivational system, what he called the attachment behavioral system, was gradually “designed” by natural selection to regulate proximity to an attachment figure.

(Source: http://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/~rcfraley/attachment.htm, ¶2-3)

My son, E., was trying to learn to survive in the wilds of our living room. I was the lion stalker, he was my prey. Then, he turned the tables on me and became my tamer, his little hands on my face taming me instantly. He also appeared to tame his own fear.

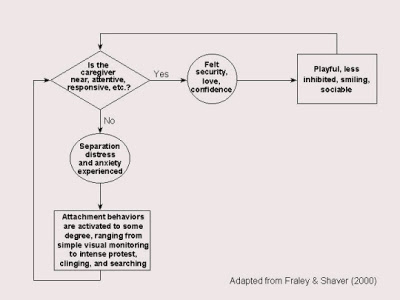

We were enacting the age-old drama associated with natural selection which requires that we learn to survive danger, seeking comfort in the arms of key attachment figures or at least camouflage in community. E. developed a game that helped him trigger not only the hormonal cascade of fight-or-flight chemical messengers, but also activated the attachment feedback loop that Bowlby, Ainsworth, and others today still observe that helps to regulate and restore limbic homeostasis: